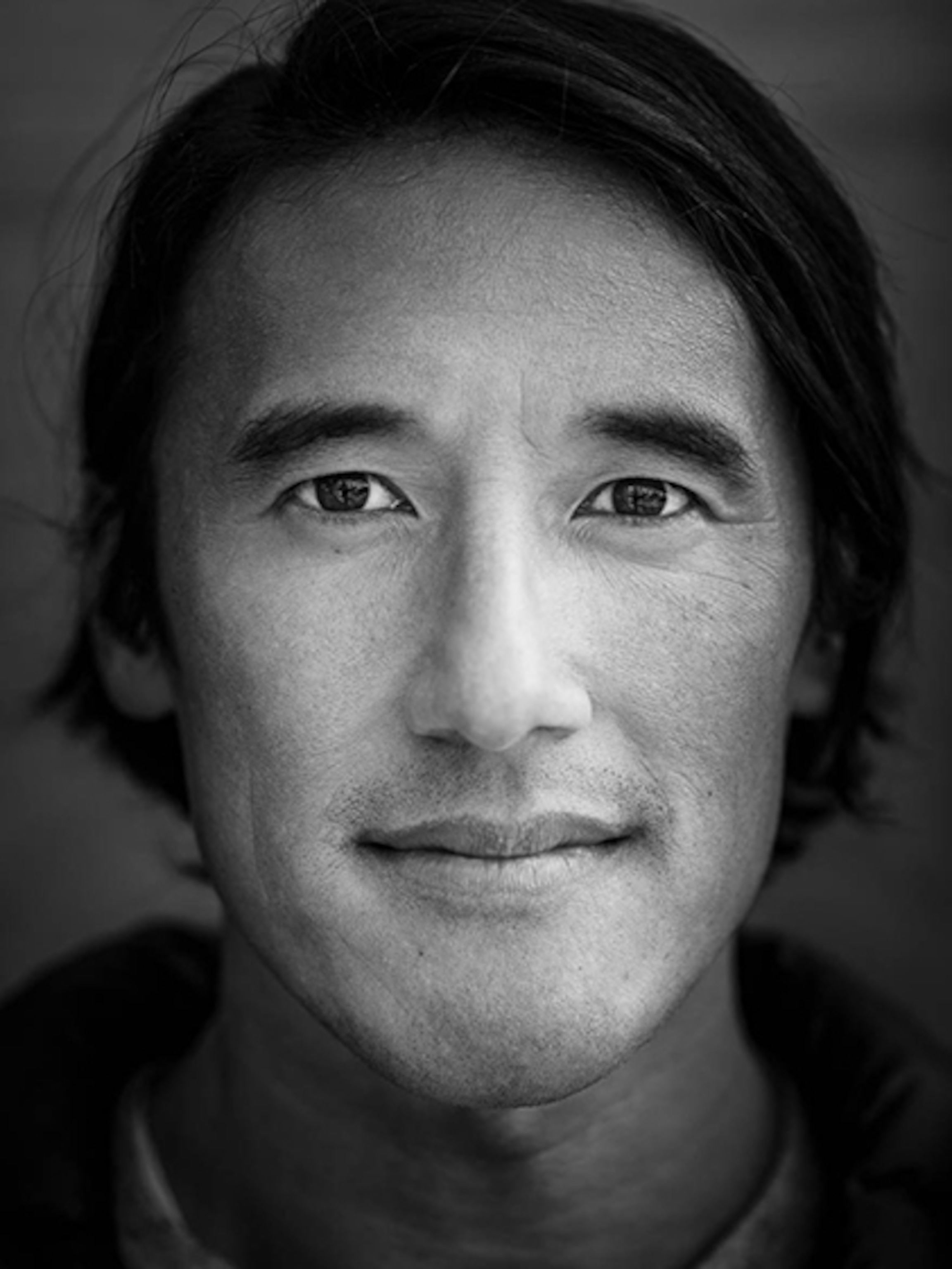

Adventure Filmmaker Jimmy Chin Talks Risk, Fatherhood, and Fame

This famed photographer and filmmaker shares thoughts on tackling risk, balancing expeditions and home life, and how climbing made him a better person.

From humble beginnings in midwestern corn country, Jimmy Chin has risen to become one of the world’s most accomplished adventure photographer-filmmakers, and his magnum opus, Meru, debuted in cinemas nationwide—a rare instance of a climbing documentary breaking out to reach mainstream audiences.

It’s the story of one of the greatest climbs of our generation up a mile-high fang of rock and ice jutting from the side of a 21,000-foot sacred peak in northern India. It’s a tale of friendship, loyalty, obsession, and a climb so far out on the fringe of human potential that only the protagonists themselves could document it. Meru is also the story of Jimmy Chin, a guy who has hidden behind his camera for years, choosing to tell other people’s stories rather than his own. On Mount Meru, Jimmy’s partners Renan Ozturk and Conrad Anker turned the camera on him, shedding a bit of light, finally, on what makes this remarkable and enigmatic man tick.

I’ve known Jimmy for nearly 20 years, dating back to the days before the sponsors, the magazine covers, and his 700,000 Instagram followers—back to when he was just another random up-and-coming climber embracing the dirt-bag lifestyle. He’s always been a man of few words, and although we’ve teamed up on four international expeditions and spent months together in jeeps, boats, tents, and hanging on the side of remote cliffs, I’ve rarely heard him speak about himself. (Read a profile of Jimmy Chin.)

So I tracked him down at his home in Jackson, Wyoming, and pressed him to tell me more about life on the wall, mud hawks, his breakup with the Camp4 Collective, and how he’s recalculating his risk calculus now that he’s a husband and father.

I just watched the clip of your portaledge tour, which was totally classic. Tell me more about your home away from home.

That’s a piece of footage that isn’t in the Meru film that we custom produced for National Geographic. It was shot at around 20,000 feet at our highest camp on the wall, just before we went for the summit. On our first attempt on Meru in 2008, we had a double portaledge with a hammock strung underneath for the third guy. But it turned out to be way too cold in the hammock so we had to stuff all three of us on the upper bunk. It was really uncomfortable, so in 2011 Conrad brought a custom built ledge that had a bed that was big enough for two-and-a-half people.

There were three of you, so how tight was it?

It’s tight enough where you usually have someone’s feet on your shoulders while you’re sleeping. If one person moves the whole ledge moves around. The most comical is at night when you’re getting into your sleeping bags because everyone has to brace and work together.

So I guess it’s important to choose your partners wisely…

Well, it’s not like finishing a game of golf and heading to the 19th hole. At the end of a day of climbing on the wall you crawl into this really small, fetid, dank, stinky confined space suspended thousands of feet off the deck. Then you spend hours melting water, making dinner, and trying to rest.

But you look forward to getting back to the ledge don’t you?

Totally. While it sounds like it’s claustrophobic and terrible in there, it’s really your safe haven. You zip up the door, and it’s the first time all day you’ll feel comfortable and warm. And usually you can take a break from being scared for a little bit – unless it’s storming really heavily. During one really bad storm in 2008 the wind blowing up the wall actually lifted the portaledge with everyone in it. When the wind died, the ledge would suddenly drop and hammer down so hard on the anchor that it felt like it was going to rip off the wall and send us plummeting to our deaths. It was Renan’s first alpine big wall, so every time we experienced something new and terrifying, Conrad would joke, “OK, Renan, now you have your ledge lift patch.”

Tell me about Phil?

Phil was a critical member of the team. We had him in 2008, and I think we brought the same exact one in 2011. To save weight, we didn’t each bring our own Phil. You know you’re getting pretty tight with your climbing partners when you’re sharing a pee bottle. The etiquette is that you immediately empty it out the door after you’ve filled it. And you are only allowed to throw it out of one side because the other side is for collecting snow for drinking water. You also always make sure you clip it back up in the middle so everyone can reach it. You don’t want to clip it in your side of the tent where the person on the far side of the tent can’t reach it in the middle of the night. That’s bad form.

What about number two?

The number one rule for number two is never go above anyone or above camp. We’d usually rig a rope outside the door of the portaledge, which you’d use to rappel down about 50 feet, drop your pants and air mail it.

Do you have a name for this, too?

Yeah, we call it the mud hawk. It could be a mud condor if you eat a lot of freeze-dried food the night before.

In the recent New Yorker piece it says that you live in Jackson and your wife and Meru co-director Chai Vasarhelyi lives in New York. How does that work living in two different places when you’re newly married and you have an 18-month-old daughter?

The general rule of thumb is if I am able to be in Jackson for more than two weeks they will come out to visit. I travel a lot, but when I have time to stop somewhere I’ll often go to New York. In the last two years I’ve spent a lot of time there. But Chai understands that I can only handle New York for about a week at a time.

A lot of people struggle to find balance between their relationships and their careers, myself included. You travel more than anyone I know, so how do you make it work. Do you have any secrets you can share?

Chai and I both have careers. She has to be in New York for her work as a documentary filmmaker, and I have to be in Jackson to train and to get some peace of mind. There are parts of New York that I really enjoy, and parts of Jackson that Chai really enjoys, so looking at it positively we feel lucky that we have the best of both worlds.

Do you feel like you do a good job of balancing it all? How big of a challenge is this for you?

It’s a challenge on a lot of levels. Obviously I wish we could spend more time with Marina and Chai. A lot of people travel for work, but it’s especially difficult when you have two different homes. But we’re both accepting of it, and we’re committed to making it work. I think we both imagine our children having exposure to both worlds, and that’s that an incredible way to grow up.

So Jimmy, you’re referring to your children in the plural form. Is there another little Chin in the works?

Yes, there is another bun in the oven. The baby is due mid December, and it’s a boy.

Wow, that’s rad, Jimmy. Congratulations. This kid is going to be so scrappy! You gotta treat him just like your pops treated you – no free pass on this one dude. That little guy is going to be chopping a lot of wood!

I know. Everyone says that having a second is really life changing. With the first one you’re so sensitive to the baby, but the second one…it’s just different. Maybe because we are just so slammed right now.

I know it sneaks up on you slowly, but I think people are really interested in how parenthood impacts people who do dangerous, extreme things like alpinism and ski mountaineering. Philosophically, do you look at risk differently now that children have been added to the equation?

I would say philosophically you do have to look at it differently. Conrad says we’re not like fireman or soldiers being called off to war or to the call of duty, so we really carry the weight of the decisions we make.

You mean because alpinism is voluntary and you don’t have to take the risks?

Yeah. And people have some very strong opinions about it. It’s hard to take people seriously who say you’re totally irresponsible if you go out and climb mountains when you have kids because they clearly don’t understand the circumstances. You can’t impose your own acceptance of risk on other people—that’s not fair.

Having a child changes the risk calculus for sure, and the level of risk will change for me, but everybody has a different threshold for risk. I see comments like this all the time directed at the film. Someone will watch the trailer and say that if you have a wife and kids and you’re climbing these mountains you’re a bad person. But the thing that I’ve always believed is that you have to follow your passion, and if climbing is your calling in life and your craft, to not do it is a tragedy. I am always going to encourage my children to follow their passions and dreams, whatever they are.

You talk about the two sides of the equation. One side is the risk and, of course, in climbing you’re risking it all. The other side of the equation is the reward, which is what makes the risk worth taking. I know this is a really hard question, and there may not have ever been a climber who has answered this question well, but what is the reward? Or in other words, why do you do it?

There are so many different levels and the answer will always be very personal. Climbing is kind of a strange pursuit—it’s an endeavor where you can slowly build up your skills toward the goal of doing something that might seem impossible. But there’s intense personal gratification in finding a mountain and becoming inspired by the aesthetics of an unclimbed line on that mountain, especially if that line has been tried by a lot of people who couldn’t do it, and you get to set yourself up against the history of it of it. It becomes this creative, intellectual, and intensely physical process that has so many different layers. And what happens is that through the course of the pursuit there is so much to be learned about yourself. And the relationships and friendships with your climbing partners become very powerful. It’s an incredible experience when you are part of a team that becomes greater than the sum of its parts. And I really believe that as human beings we have an innate need to explore, to see what’s around the corner.

Do you think everybody has that need?

I can’t tell how much of it is nature versus nurture, but absolutely everybody has it to different degrees. But it can be repressed or pushed down, and not everybody embraces it.

So how do you respond when people criticize climbers like yourself, Tommy Caldwell, and Alex Honnold because of the risks you take?

I used to get really fired up when I saw that stuff, but now I just don’t have time to worry about it. In a way I feel compassion for them because if they really don’t understand it then I feel like they are really missing out on something important.

I think it’s fair to say that our innate need to explore and to push the boundaries of what’s humanly possible is right at the essence of what makes humankind great.

Yes. That’s so true. The need to explore is something that’s always been so central in my life and something that’s given my life meaning. And honestly—that’s a big part of my motivation for making this film. We wanted to show what the stakes are and that the decision making process is very complex. A lot of the film is an examination of decisions and what’s at the core of those decisions.

You are both a photographer and a filmmaker. Do you find that film is a better medium for telling complicated stories?

Yes, film is a very powerful medium. It’s got visual elements, narrative, audio, and music, and it works with so many of your senses. When it’s done right, film can say something that’s really hard to say any other way. There are some stories I couldn’t do justice to with just photography, and I don’t think I could do it as a writer.

Is this one of the reasons we see you moving more and more into filmmaking?

Yes and no. I kind of fell into filmmaking the way I fell into photography. It started when I was invited to join an expedition to the Changtang Plateau in Tibet in 2002. Rick Ridgeway, Conrad, and Galen Rowell invited me to take Dave Breashears place as the expedition cinematographer when he had to drop out—even though I had never filmed before. I spent months on that expedition being mentored by Rick, who had won multiple Emmys and worked on a number of feature length films. He really held my hand through the entire process: why I was shooting, what was important to shoot, how to shoot sequences and scenes, and how to think about a story when you’re a participant in the story. And then after the trip we spent months editing and assembling all the footage into a film. Then the next year I spent three months on Everest with David Breashears and Stephen Daldry shooting what was the initial production of the upcoming Everest feature film that is about to release. So those two years stacked right on top of each other with two incredible mentors. Soon after, I worked on several other feature productions with directors Anthony Geffen, Chris Malloy, Danny Moder and others. They all greatly influenced me in one way or another. Working with them on bigger budget productions helped me to understand all the moving parts and aspects of filmmaking beyond the shooting – i.e. producing and directing.

I know it’s a sensitive subject, but would you be willing to say anything about why you left Camp4 Collective?

I’d prefer not to go into it, but I am happy to say that I founded Camp4 with Tim Kemple and Renan Ozturk in 2010. We brought in Anson Fogel a couple years later, and I left the company in 2013.

A lot of us saw the promo reel that Camp4 published after you left which told a story of how the company was founded, a story in which you didn’t have a part. So I have to ask: Was it kind of annoying when you saw it?

What can I say? I moved on a while ago. It was the best decision of my career to leave and most of the people whose opinions matter know my part in Camp 4’s genesis.

Was there anything good to come out of your split with Camp4?

When I left, I took Meru with me. I had to start a new production company around the film. I think it’s easy to look at the film now and think it’s been an easy road but I had to fight a long fight for the survival of it. There was a time when it was dead in the water, with no support from anyone, no financing and a lot of personal doubt around it. I had to go out and convince people it was worth something and find private investors. Thankfully, I teamed up with Chai to co-direct the film. We decided to rewrite the film and reshoot all the interviews. We looked closely at what we wanted the film to say, and really examined how to rebuild it structurally. I think there is a misperception that having all the elements of a great story equates to having a great film. You can have all the most intriguing plot points in the world but still have a bad film. The craft is in the structure, in creating the clarity of the narrative, using restraint, balancing timing and when you reveal information, how you reveal it etc. I needed to work with people who had a broader perspective. So I guess you can say that the silver lining to the breakup is the film itself and how it has turned out. Personally, the process of making the Meru film has been the most gratifying experience of my career.

You’ve talked about how being an alpinist has helped you to grow as a person. What have you learned over the eight years you’ve spent working on the Meru film?

Just like on a climb, what I learned is that I could never have done this by myself. I made my contributions, but this film would not be where it is without a lot of other people, most especially Chai. She came in as a force of nature. She has directed five feature length documentaries and has 15 years of experience, and she leveraged all of that to get Bob Eisenhart to edit the film. Never in a million years would I have been able to get Bob Eisenhart. Everything that went on behind the scenes can be easily lost when a film is well made because you don’t want people to see and understand what went into it. It needs to play with a certain ease—but there are no happy mistakes in this film.

What is the single most important attribute you look for in a friend?

Loyalty and integrity. But it’s not blind loyalty—you have to earn loyalty. I won’t say I go out and search for people with these traits to become my friends, but with all of my close friends there is a deep sense of loyalty and trust.

What is it like to be famous?

I really don’t think of myself as being famous. I was just in L.A. hanging out with Justin Timberlake and Matt Damon—now those guys are famous.

Yeah, and you’re hanging out with them…

[Laughing] Well…I don’t need a security team just to go for a walk. There may have been a time in my life when being well-known was an attractive thing, and I don’t know if it’s because I’m getting older, but I’m really kind of ambivalent about it. What I like to think about is the fact that the Meru film will outlive me, and that I’ve created something that said what I wanted it to say. This film is the culmination of my life’s work, and it feels incredibly satisfying to now be able to share it.

So what’s next? You don’t seem like the type to rest on your laurels….

Raising great children is my next life’s work … and, we’re in development on another film. I can’t say anything more right now, but I’m sure you’ll be hearing about it.

You May Also Like

Go Further

Animals

- What La Palma's 'lava tubes' tell us about life on other planetsWhat La Palma's 'lava tubes' tell us about life on other planets

- This fungus turns cicadas into zombies who procreate—then dieThis fungus turns cicadas into zombies who procreate—then die

- How can we protect grizzlies from their biggest threat—trains?How can we protect grizzlies from their biggest threat—trains?

- This ‘saber-toothed’ salmon wasn’t quite what we thoughtThis ‘saber-toothed’ salmon wasn’t quite what we thought

- Why this rhino-zebra friendship makes perfect senseWhy this rhino-zebra friendship makes perfect sense

Environment

- What La Palma's 'lava tubes' tell us about life on other planetsWhat La Palma's 'lava tubes' tell us about life on other planets

- How fungi form ‘fairy rings’ and inspire superstitionsHow fungi form ‘fairy rings’ and inspire superstitions

- Your favorite foods may not taste the same in the future. Here's why.Your favorite foods may not taste the same in the future. Here's why.

- Are the Great Lakes the key to solving America’s emissions conundrum?Are the Great Lakes the key to solving America’s emissions conundrum?

- The world’s historic sites face climate change. Can Petra lead the way?The world’s historic sites face climate change. Can Petra lead the way?

History & Culture

- Hawaii's Lei Day is about so much more than flowersHawaii's Lei Day is about so much more than flowers

- When treasure hunters find artifacts, who gets to keep them?When treasure hunters find artifacts, who gets to keep them?

- Meet the original members of the tortured poets departmentMeet the original members of the tortured poets department

- When America's first ladies brought séances to the White HouseWhen America's first ladies brought séances to the White House

Science

- Should you be concerned about bird flu in your milk?Should you be concerned about bird flu in your milk?

- Here's how astronomers found one of the rarest phenomenons in spaceHere's how astronomers found one of the rarest phenomenons in space

Travel

- Are Italy's 'problem bears' a danger to travellers?Are Italy's 'problem bears' a danger to travellers?

- How to navigate Nantes’ arts and culture scene

- Paid Content

How to navigate Nantes’ arts and culture scene - This striking city is home to some of Spain's most stylish hotelsThis striking city is home to some of Spain's most stylish hotels

- Photo story: a water-borne adventure into fragile AntarcticaPhoto story: a water-borne adventure into fragile Antarctica